The Life of Raja Rao

"I was born in a dharmashala, ... in (the town) Beautiful, Hassana... from a family that can boast of having been Vedantins at least since the thirteenth century, and again brahmin advisers to kings, first in Rajputana, another thousand years earlier, and yet again brahmins to other kings, maybe the Greco-Indian ones in Gandhara, earlier yet--at least such our mythical genealogy tells us... My mother, not finding enough room in our ancestral home for lying-in, had to be transported to the dharmashala, room number 1, and hence when my father was offering the prescribed 'half-cut lemon on the knife'... my mother was so vitally shaken she threw me into the world, hence instead of being named Ramakrishna, like my grandfather was, I was simply called Raja.

My grandfather taught me Amara, that wonderful thesaurus which, like a grave and good brahmin boy, I had to learn by heart, and thus never had to ask who the Two-mothered One is, of course he is Ganesa... Life would not be worthwhile if you did not know which God was what...

Now then, I had also to be educated in the modern manner, consequently every summer (duly accompanied) I started going to my father who was in Hyderabad, five hundred long miles away... because one of my grand-uncles became a lawyer, and an adviser to many of the Hyderabad rich, so that my father came to him to stay with and to study, and I went of course in the wake of my father.

And this was how a South Indian brahmin boy entered the Madrasa-e-Aliya, a school meant mainly for Muslim noblemen, the only Hindu in my class. ... Though the Goddess Laksmi was so generous to us in Hyderabad, and the school kind... I developed some chest trouble, and the doctors asked me to go back to my home-mountains, where I went, this time to my sister, to that hallowed place of pilgrimage, Nanjangud, on the river Kapila--I lived just behind the temple, among priestly brahmins, I a student of... Aristotle.

...august forces took me to Aligarh and to the Muslim University. There I was once more a student in an Islamic institution... and here it was... I first heard of Arles and Avignon, of Michelangelo and of Santayana. ...later when I went back to Hyderabad, I continued to be involved with literature till one day, a letter came in a blue envelope (I still remember) from Sir Patrick Geddes, who said he had established an international college at Montpellier, and since he liked what little he'd seen of my writing, 'So, why not come?'... straight I went to Montpellier...

And France was so much like India, formal, friendly, and full of the beaux desordres--the Indian desordres were not even beaux. I was impressed too by the self-reflectiveness of the French language, by its severe musicality... Now I went back to my Kannada [language], wrote a few things in my classic native tongue and published them... and emerged out of this holy dip a new man, with a more vigorous and, maybe, a more authentic style. ... I lived thus with France, and France gave me back my India.

A South Indian brahmin, nineteen, spoon-fed on English, with just enough Sanskrit to know I knew so little, with an indiscrete education in Kannada, my mother tongue, the French literary scene overpowered me. If I wanted to write, the problem was, what should be the appropriate language of expression... Sanskrit contained the vastest riches of any, both in terms of style and word-wealth, and the most natural to my needs, yet it was beyond my competence to use. ... French, only next to Sanskrit, seemed the language most befitting my demands, but then it's like a harp (or vina); its delicacy needed an excellence of instinct and knowledge that seemed well-nigh terrifying. English remained the one language, with its great tradition... and its unexplored riches, capable of catalysing my impulses, and giving them a near-native sound and structure.

I was to write... my English, yet English after all--and how soon we forget this--is an Indo-Aryan tongue. Thus to stretch the English idiom to suit my needs seemed heroic enough for my urgentmost demands. ... So why not Sanskritic (or if you will, Indian) English? ...to integrate the Sanskrit tradition with contemporary intellectual heroism seemed a noble experiment to undertake. Thus both in terms of language and of structure, I had to find my way, whatever the results. And I continued the adventure in lone desperation.

When I published my first stories in Europe... Romain Rolland and Stefan Zweig wrote enthusiastic letters to me about them. And Kanthapura, my first novel, was mostly written in a thirteenth-century castle of the Dauphine in the heart of the Alps, and when it came out, E.M. Forster spoke so boldly of my rigour of style and structure, I had, so to say, entered the literary world."

--Excerpts from "Entering the Literary World," by Raja Rao, copyright 1978

A Raja Rao Retrospective

Raja Rao leans forward, his eyes intent. "Ask me any question," says the old, slightly lilting, voice. "Go ahead. You can ask me anything."

This unusual invitation comes from one of India's finest writers in English, the 1988 winner of the prestigious $25,000 Neustadt International Prize for Literature. The books Rao has written and the books by others published in India analyzing his novels, fill two shelves in the Perry Castaneda Library at The Universtiy of Texas. ... Rao knew Gandhi and Nehru. In India he would be, as he puts it, "somewhat important." But he chooses to live in Austin [Texas]. ...

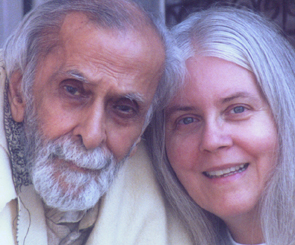

Rao, whose third wife Susan was a University of Texas student in the '70s, says that though he lives in Austin he has in fact never left India. "India is my home; there is no question." Does Rao write better about India, living outside of it?

"No, I don't think so, India is everywhere. Look at my house," he says, glancing at an Indian picture. "Look inside my books in my room. It's all very Indian."

Does he write to translate India for the West, then, as some critics have suggested?

"No. I just do it for myself. I make no concession to the West. Right, Susan?"

His wife of 12 years laughs. "Oh, absolutely. In no way, at any time."

Rao has two sons, both born in Austin but now living in St. Louis and India.

Rao defines the major theme of all his fiction as the search for the truth; man's search for ultimate values. It is a search that has consumed much of his life.

Rao grew up in Mysore, an area of coffee plantations and famous old temples, in the south of India. He was a member of an old and respected Brahmin family. He did not study fiction writing, but came to it naturally. "I wrote as a man of sixteen or seventeen," Rao says. "I wrote in English. I was sent to a very snobbish English school. I learned English from English people in India. I learned Sanskrit much later."

His father was a scholar and professor. But it was from his grandfather, who spoke not a word of English and meditated at length, that Rao got his philosophical bent. "My grandfather started me on the search," he says. "Philosophical inquiry is personal contact. Not merely philosophical thinking. Indian philosophy is thought in the West to be mystical. But it's really logic. Logical and metaphysical."

He went to the Aligarh Muslim University and to Nizam's College, Hyderabad, in India. At the age of nineteen, he went to France, where he studied at the University of Montpellier and later at the Sorbonne. He left France in 1939, fifteen days before the outbreak of World War II. "If I'd been there fifteen days more, I'd not be alive today," he says, because of his opposition to Hitler. "I was just lucky. When I got to India, I went straight to a sage."

"France, to my mind, is still the heart of Western civilization," Rao says. His first wife was a professor of French, and for about thirty years he lived six months in France; six months in India. For a time he considered becoming a monk.

His first novel, Kanthapura, about a village in South India affected by the spirit of Gandhi, was published in the United States in 1938. The Serpent and the Rope was published here [in the U.S.] in 1960. Other works include a collection of stories written earlier, The Cow of the Barricades, but published in 1947; The Cat and Shakespeare in 1965; Comrade Kirillov in 1976; The Chessmaster and His Moves in 1988. In the years since, Rao had been working on a sequel to this last novel, which has Indian Vedantic philosophy at its core.

"I became a professor here [in Austin] in 1966," Rao says. "I had never taught before...," he smiles. (At the time he was married to Catherine Jones, an actress.)

"In the '60s and '70s the search for values was very remarkable. I was really thinking America would be the greatest nation..." Rao points out that America had been fascinated by India even earlier. "The 19th century transcendentalists--Thoreau, Whitman, Emerson--were all influenced by India. The pragmatic American, I think, has not got time for India." These days Rao sees less interest in the philosophical. "Most of modern literature is psychological," he says. "There is no search in it. Philosophy began to go down in '78 and '79."

Rao feels he has found answers to his philosophical searching through meditation and long study with a guru in India. He sees the West in a state of great gestation. "The West has not reached its destiny," he said.

--excerpted from an article by Anne Morris, Austin American-Statesman, 1997

Chronology

1908 born on November 8 in Hassana, Mysore, India

1912 mother, Gauramma, dies

1915 enters school in Hyderabad

1925 graduates from school in Hyderabad

1926 studies English and French

1927 studies at Nizam's College, Hyderabad

1929 graduates with a B.A. in English and history

receives Asiatic Scholarship for study abroad from government of Hyderabad

begins studies at the University of Montpellier in France

1931 writes in Kannada for an Indian periodical

researches Indian influences on Irish literature at the Sorbonne

1932 serves on editorial board of Mercure de France, a Paris periodical for 7 years

1933 returns to India to live in Pandit Taranath's ashram in Tungabhadra

publishes first stories in French and New York periodicals

1938 publishes first novel, Kanthapura

1939 meets Sri Aurobindo in his ashram in Pondicherry

lives in Ramana Maharshi's ashram in Tiruvannamalai

edits Tomorrow, a bombay periodical until 1940

1940 father, H.V. Krishnaswamy, dies

1942 lives in Mahatma Gandhi's ashram, Sevagram

active in underground movement against the British

1942 meets his guru, Sri Atmananda, in Trivandrum

1944 publishes stories in Indian periodicals through 1947

1947 publishes The cow of the Barricades and Other Stories

publishes Indian version of Kanthapura

1948 returns to France

1950 visits U.S.

1953 publishes story in London periodical

1958 travels in India with Andre Malraux, de Gaulle's emissary to Nehru

1960 publishes The Serpent and the Rope in London

1963 publishes stories in Bombay periodical

publishes U.S. editions of Kanthapura and The Serpent and the Rope in New York

1964 receives Sahitya Akademi Award from the government of India for The Serpent and the Rope

1965 publishes The Cat and Shakespeare in New York

publishes French version of Comrade Kirillov in Paris

1966 begins teaching Indian philosophy at The University of Texas

1968 publishes Indian edition of The Serpent and the Rope in Delhi

1969 honored by the government of India with the Padma Bhushan

1972 named a fellow of the Woodrow Wilson International Center, Wash., D.C.

1978 publishes The Policeman and the Rose: Stories in Delhi

1980 retires as Professor Emeritus from The University of Texas

publishes Malayalam version of The Cat and Shakespeare

1984 elected an Honorary Fellow of the Modern Language Assn. of America

visits Japan

1988 named tenth laureate of the Neustadt International Prize for Literature

publishes The Chessmaster and His Moves in Delhi

1989 publishes On the Ganga Ghat in India

1996 publishes The Meaning of India in India

publishes Hindi translation of The Serpent and the Rope in India

1997 presented with the Sahitya Akademi Fellowship, India's highest literary honor

The Word as Mantra, a one-day symposium on his works is held at The University of Texas

1998 publishes The Great Indian Way: A Life of Mahatma Gandhi in India

Chronology compiled by R. Parthasarathy.

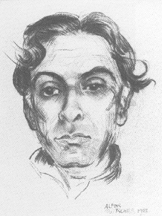

Photos 1. age 10, 1918 2. France, 1932 3. drawing, 1958

4. 1980 5. 1988 6. with wife, Susan, 2001

HOME HIS LIFE HIS WORK

HIS PHILOSOPHY HIS ART TRIBUTE RAJA RAO PROJECT

BOOKSTORE CONTACT US LINKS